First published in the Santa Barbara Sentinel under the pen name, Elizabeth Rose. (Chris is known as “Jason” in the I Heart columns.)

After sailing to Topolobampo, Mexico, Jason and I took a bus to Los Mochis then an eight-hour train ride to the Copper Canyon (or, Barrancas del Cobre) in the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains.

As we stepped off the train in a little town called Divisadero, we were submerged into a sea of people and vendors selling hot food, crafts, and souvenirs.

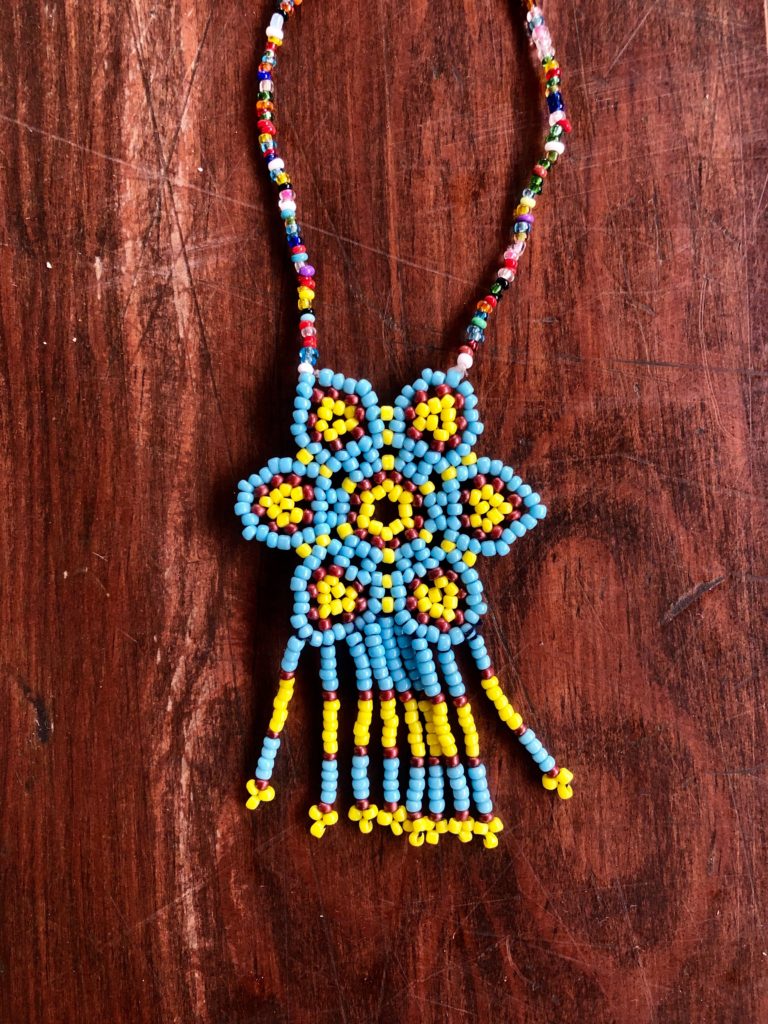

The Raramuri (or Tarahumara) indigenous women, wearing floral-printed skirts and vibrant long-sleeve blouses, sat behind tables loaded with beaded necklaces, woven baskets, vibrant scarves, wooden spoons, and carvings.

The same scarves were tied around their hips for warmth and fastened to their backs, carrying a young one inside.

Little girls ran to tourists with necklaces in their hands, singing, “Quiere comprar?” in a nursery rhyme sort of way, rolling off their tongues like they had done it a hundred times before.

With backpacks on, we shouldered through the crowd down a long walkway that opens to the canyon rim.

The canyon’s breadth was hard to register with the eye, looking more like a backdrop for an old Hollywood western than actual real life.

The sun behind white clouds cast dark shadows on the canyon walls, the massive rock striated in aged shades of brown.

Following a dirt path near the edge of the canyon, we walked directly through a community of four small houses no more than fifty feet from the ledge.

A little girl, about the age of four, sat under a clothing line strung with colorful handmade garments, smiling curiously as we strolled by.

A rooster pecked a few weeds, then crowed.

A woman, possibly her grandmother, stepped out of a hut to usher the little girl back inside.

For the next few days, we wandered Divisadero and a nearby town, Creel, further indoctrinating us into their way of life and it was easy to see how different our cultures had become.

The Tara families live in small groups of houses throughout the canyon and keep to themselves, away from foreigners except to sell their wares.

Homes are simple, made from scrap wood and metal.

Some live inside of caves.

But upon touring the Tarahumara cultural museum, our similarities came to light.

Jason and I viewed black and white photographs of sacred ceremonies and captions declaring their disdain for materialism.

It was then I wondered how much modern society had shaped the views of their culture.

Though the women and children sell beautiful handmade crafts, also available are mass-produced trinkets such as wallets, cheap metal jewelry, and other souvenirs I’ve seen in Mexican tourist shops before.

It seems that even a prehistoric culture of people, who denounce materialism as a whole, can not escape it.

Because in order to make more money, they fed the materialism of others through a mix of handmade and commercial goods.

I struggle with “stuff,” and maybe you do too.

Although I’ve “KonMari’d” my parents home, currently live on a 34’ sailboat, and will possibly live in Dodge Sprinter Van, I am highly aware that I don’t have room to put things yet I still buy them.

For example, my obsession with vintage clothes is replaced with jewelry (easier to stow), and now I fold my garments in square travel bags to create room for more.

Still, with that in mind, I was at almost every table buying crafts, almost feeling a sense of duty to support the Tara’s through my desire for colorful material objects, handmade or not.

Or maybe that’s just an excuse.

I wondered if my urge to support begins and ends with the amount of souvenirs I can stuff into my bag.

Is my intention to help just way to mask my ego?

What comes first, good intentions or my desire for cool jewelry?

An Economics professor once said, “if you’re not selling something, you’re selling yourself,” a phrase that’s bounce around my head and now I understand what he meant.

As a writer who is currently figuring out ways to monetize outside of freelance writing, I wonder what value I can bring to the world that doesn’t require making a tangible product.

Is it possible?

Or does making a living in our modern world urge us to eventually produce, whether we want to or not?

What are your thoughts on materialism?